Kamen Rider Amazon, or Masked Rider Amazon, is one of the TV shows that fascinated and excited Japanese kids in the 1970s. The Kamen Rider series is a weekly sci-fi tokusatsu (live-action film) TV show based on a manga comic written by Shotaro Ishinomori, a legendary manga artist who had a huge influence on the history of the genre. Amazon, the fourth show in the series, continues to enjoy popularity among fans to this day, in spite of the brevity of its six-month broadcast run. Kamen Rider has been, and still is, an exceptionally popular superhero among Japanese kids and even adults. The series have a rigidly adhered-to structure: an ordinary Japanese youth finds himself destined to be a Rider, a superhero into whom he can henshin (transform) with a signature shout and pose when he needs to use his superpower to fight supervillains, often known as kaijin. Riders are always outfitted in cool-looking masks and bodysuits, and ride specially-equipped motorcycles, which is the source of their name “rider.” The show started with Kamen Rider, and with its popularity, was serialized into other shows such as Kamen Rider V3, Kamen Rider Stronger and Kamen Rider Super-1. The franchise still continues to produce new shows, the more recent incarnations of which are referred to as the “Heisei Rider” series. Heisei is the current Japanese era name (nengo), which began on January 8, 1989 with the 125th Emperor Akihito’s ascension to the throne. In Japan, this system is still prevalent, particularly in official documents; the current year, 2017, is counted as “Heisei 29” in this system. Last year, in 2016, or Heisei 28, when Emperor Akihito hinted at a desire to abdicate the throne with the release of his “okimochi” message, it attracted a great deal of media attention, because the Imperial Household Law does not contain a provision that allows the emperor to abdicate before his death. The era preceding Heisei is Showa, which ended with the death of Emperor Hirohito in 1989, or Showa 64. In contrast to the “Heisei Rider” series, the older Rider shows, which started in 1971, or Showa 46, are retrospectively called “Showa Rider” series, and Kamen Rider Amazon, which started its broadcast in 1974, or Showa 49, belongs to this group.

Among all the Kamen Rider series, including all the “Showa Riders” and “Heisei Riders,” Kamen Rider Amazon has the most unusual setting, and its main character is among the most mysterious of all the Riders. The protagonist is a Japanese man who was stranded in the Amazon rainforest by a plane crash in his early childhood and was raised there. On reaching adulthood, he comes back to his home country Japan as a Tarzan-like figure who is unfamiliar with civilization. Unlike typical heroes in TV shows, who are usually handsome and sophisticated, Amazon is a lonely barbarian. Unlike the other Riders, who look cool while riding their specially-equipped motorcycles and perform their signature finishing kicks with an acrobatic grace that kids can never copy in reality, Amazon always wears unfashionable shorts when he is not transformed and his finishing attack sometimes simply involves biting his enemies, which kids can easily imitate. Amazon rides his motorcycle the same way that kids ride their bikes, frequently shrieks in an insane-sounding voice and behaves violently, so his behavior is not so different from what ordinary kids do. Strange though he might be when viewed alongside the other Riders for whom looking cool is a top priority, from the persepctive of kids in the Showa era, Amazon was an extremely relatable hero.ⅰ

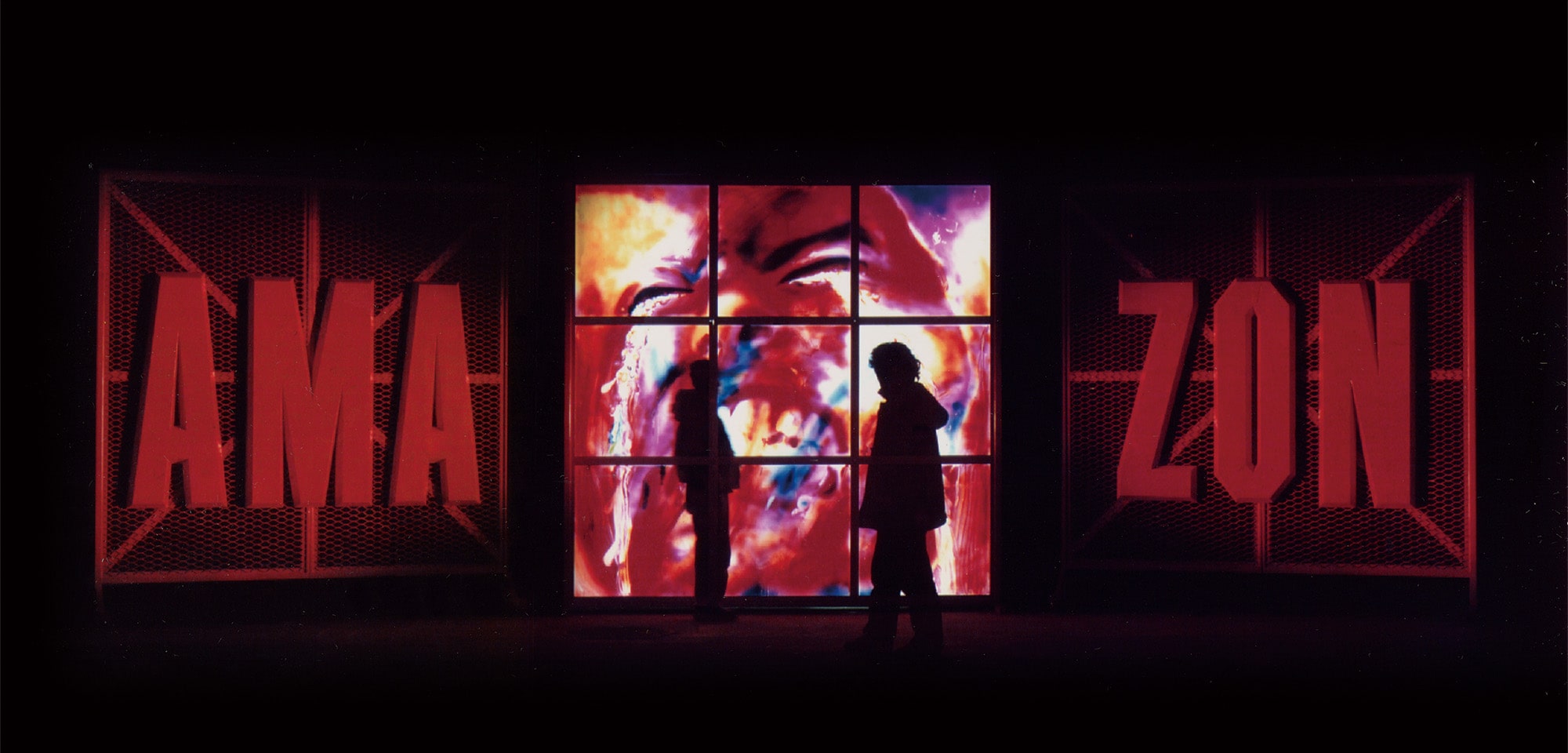

Kawai + Okamura, an artistic unit composed of Takumi Kawai and Hiroki Okamura, made their sensational debut in the contemporary art scene in Japan with a work called Amazon in 1993. It consists of a huge lightbox painted on the surface and illuminated from behind, with deep red relief-like three-dimensional characters reading “AMA” and “ZON” sandwiching the lightbox. The lightbox was made by Okamura, who majored in drawing and painting, while the character reliefs were produced by Kawai, whose specialty was sculpture. The portrait of a youth painted on the lightbox, who appears to be crying in agony through clenched teeth, is that of the protagonist of Kamen Rider Amazon before transformation, and the title of this work is also taken from the show. Of course, this work was produced before a certain huge online bookstore of the same name started their business.

Amazon (1993)

It is important to note that this debut work of Kawai + Okamura takes its subject from the Kamen Rider series, among others, Kamen Rider Amazon. Kawai + Okamura’s Amazon was first shown at an independent group exhibition by art students. At such independent exhibitions, where the larger part of the audience consists of the artists’ acquaintances, young artists tend to bring works which appeal only to insiders in the hope of immediate favorable reactions from them, thereby leaving outsiders in the dark. However, Kawai + Okamura not only nostalgically adopted a superhero well-known to kids of the Showa era, but they also depicted him as “someone who is in solitude in this country,” and it was not only the barbarian protagonist of Kamen Rider Amazon who was in solitude in this country; Kawai + Okamura were, too. They started their artistic career in the field of contemporary art, which is hugely Western-influenced, so the crying face of Amazon in agony duly reflected the situation Kawai + Okamura were in. In short, Amazon was in a sense Kawai + Okamura’s self-portrait.ⅱ

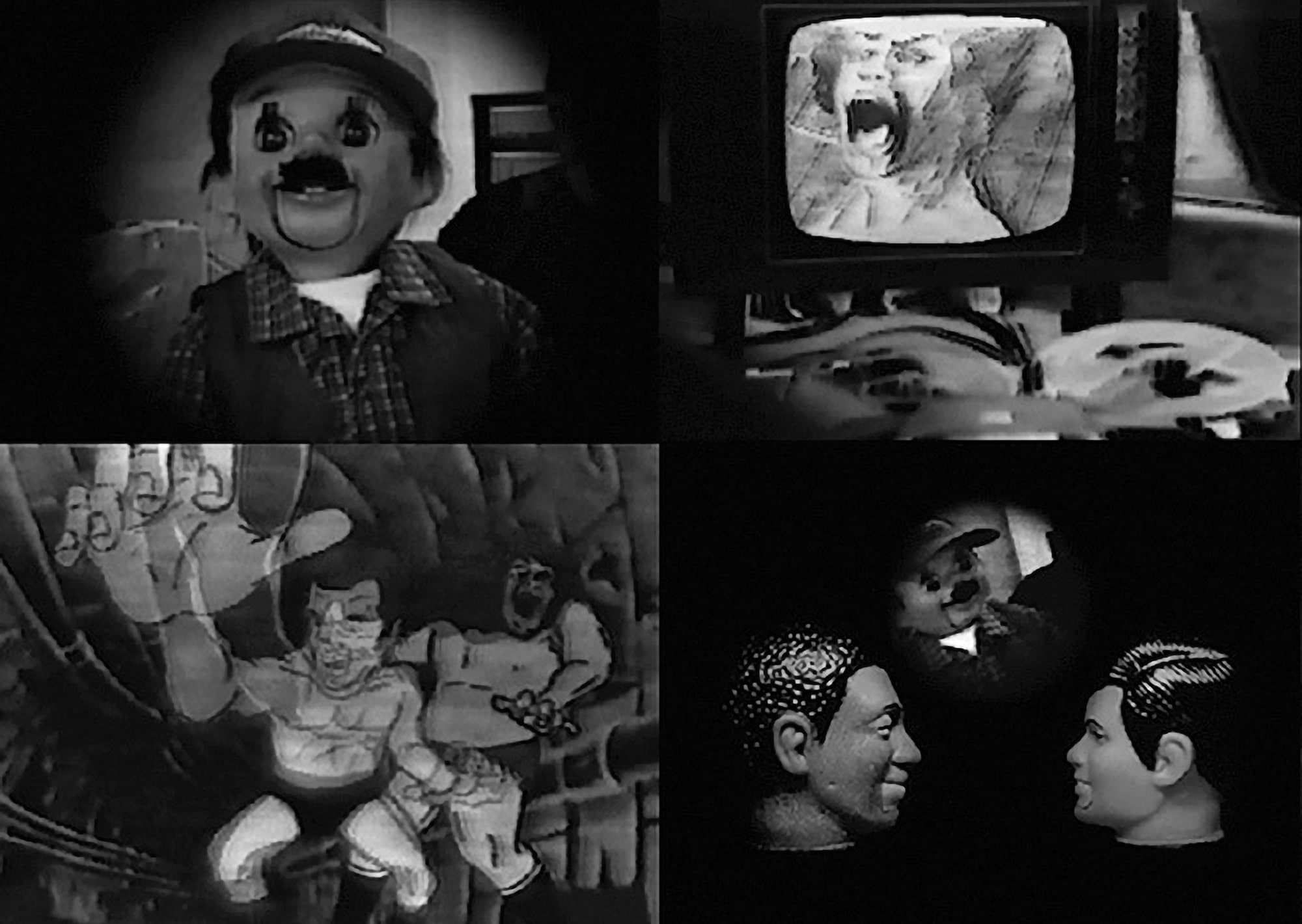

What most entranced the child audience of the Kamen Rider series every week was their protagonists’ henshin routine, in which an ordinary human transforms into a Rider who has superpowers and a bizarre appearance. Kawai + Okamura have also once undergone a “henshin” and astonished Japanese art fans. They produced and exhibited a lightbox work taller than 3 meters, called Superstar, in 1995. After two years of silence, they had their first solo exhibition, entitled Over the Rainbow,ⅲ where they exhibited only video works. After this exhibition and a succeeding solo exhibition named Shikakui Janru (The Man of the Genre Mountains)ⅳ in 1999 and their latest work— Mūdo Hōru (Mood Hall/Mood Hole)ⅴ—shown at this solo exhibition, Kawai + Okamura have gradually been recognized more as a video art unit than a sculpture/painting unit. After being awarded the Silver Dragon for the Director of the Best Animated Film at the 53rd Krakow Film Festival with Columbos(2013),ⅵ and an honorary mention at Ars Electronica in 2014 with the same work, it came to be shown at several film festivals in different countries; accordingly, Kawai + Okamura have come to be always recognized as “video artists.” After 1995, they have not created any lightbox works. They have completely henshin-ed, or transformed themselves, from a sculpture/painting unit into a video art unit.

Over the Rainbow (1997)

The Man of the Genre Mountains (1999)

Mood Hall / Mood Hole (2016)

Columbos (2012)

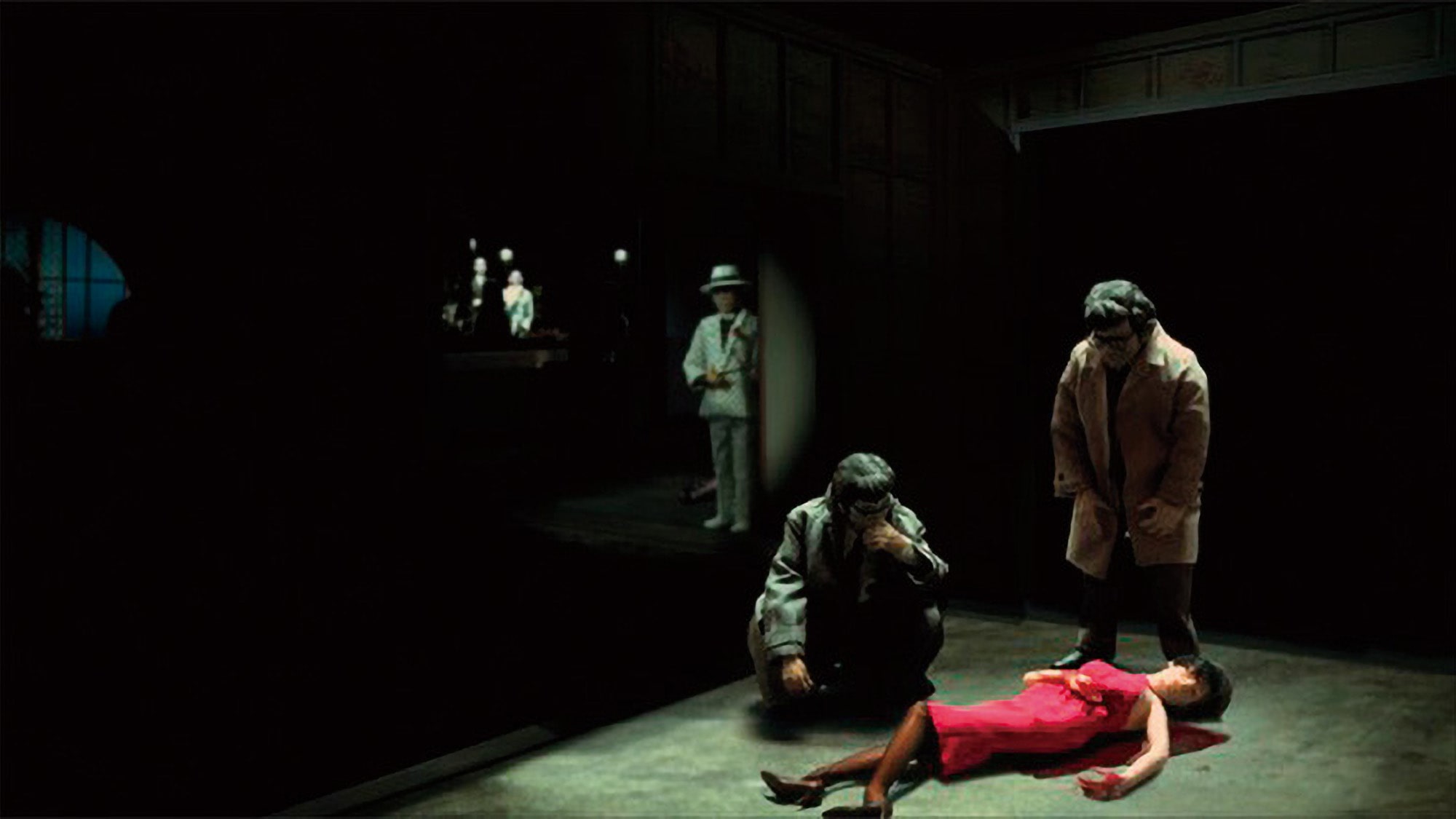

Indeed, Kawai + Okamura have increased the amount of time they spend on creating their artwork: Takumi Kawai continues to create plastic art and Hiroki Okamura keeps on painting, just like they used to do in the days when they created their lightbox works. Their plastic art and painting, however, have found a totally new place to be categorized: video art. Kawai creates dolls and Okamura paints them. The work of both artists are elaborate and painstaking enough to be exhibited by themselves. The combination and collaboration of Kawai and Okamura, or that of plastic art and painting, developed into something more complex and intricate, and changed its territory from the real and physical to the virtual and metaphysical.

Kawai + Okamura have not revealed how they create their artistic works together, but judging from these works, it is safe to say that neither of them works independently when they write scripts, shoot and edit the video, and overdub the music.ⅶ One way to think about their collaboration is to compare them to a tag team in pro wrestling, one of Kawai + Okamura’s favorite pop culture genres. Pairs of wrestlers are often divided into two types: those in which the abilities of the two wrestlers are simply added together, and those in which they are multiplied, in which the two wrestlers together create something greater than the sum of the parts. Seen through this lens, Kawai + Okamura’s earlier lightbox works were simple addition, whereas in the field of video art, the abilities of the two artists are multiplied, creating something much more complex and interesting. Because of this multiplying collaboration, the workload and the time they spend in creating their works has also multiplied significantly. This fact reminds me of Kamen Riders again: they always had to work much harder after they had henshin-ed, or transformed, for they had to defeat their enemy kaijin in limited time, using every ounce of their skill and energy. However, the harder the Riders worked, the brighter the eyes of the kids watching them turned and they got attracted to the show more and more. This must be the case with Kawai + Okamura as well; you can see how bright the eyes of the audience are at their exhibitions.

Kawai + Okamura often compare their artistic creation to playing with dolls. Their animation work, in which they place tiny dolls in a miniature set and keep on shooting them in stop motion while moving them little by little, resembles playing with dolls, to be sure, and it also reminds us of the way we played with Kamen Rider figures when we were kids enjoying the shows, or pretending to be Riders with other kids after school in the field. What is characteristic about Kawai + Okamura as a video artist unit is that spirit of “play,” which leaves us the impression that they are still, in some sense, back in the good old days. However long you might stay in that golden period of childhood when we enjoyed TV shows, films and comics like Kamen Rider Amazon, The Wizard of Oz, Columbo and Shikakui Janguru (Square Jungle), you cannot find yourself having grown up and being in the adult world at all. Yes, we know that there are no adults at all. Not a single one on the face of the planet. I have no doubt that Kawai + Okamura, the Kamen Rider Amazon of the contemporary art world, who manage to keep staying in that nowhere connected to the good old days of childhood, must be thinking about this while creating their art.

Superstar (1995)

Photo: Yasushi Ichikawa